May 15, 1999

Jerusalem, bethlehem & hebron

Towards the end of my stay in jerusalem, my blunt and curious german friend from berlin has come to join me in rehavia at the moravs, my diplomatic hosts and friends. not being one to beat around the bush, he quickly invites me to accompany him to the west bank in his mercedes benz. now “benny”, nee “hans”, was born to a family sympathetic to hitler and the nazis during the war. having made a small fortune in berlin in various alternative lifestyle fields, and now approaching forty, benny is understandably, more than a little fed up with his native countrymen, their history, economics, politics, and constant flirtation and realignment with, the right. as such, he’s recently changed his name, come to LA, studied torah and zohar at the kaballah center on robertson with madonna and roseanne, and is now on a personal mission to learn hebrew in the holy land. and to immerse himself in what he has determined to be the world’s finest religion, judaism.

A fair-skinned, wispy-haired, tall but slightly-built, be-spectacled scientist-type, benny knows more about the jewish holy sites in the land of israel and their rabbinical history than anyone needs to know. he can spout off the names of scholars, tzaddiks (mystical jewish leaders), rabbis, and holy men faster than i can remember the names of my great uncle herbie and his mother ethel. in fact, benny is probably more “jewish” than i am, despite his not being circumcised, not having converted, nor his mother being born jewish (the only way jews recognize and accept one unto their tribe).

Bethlehem photo by Joseph Giove III, www.highrock.com

Bethlehem photo by Joseph Giove III, www.highrock.com

But here benny and i are driving to bethlehem, the place where little baby jesus was born and where the three wise men rode their camels to find mary and joseph at the manger. we both know at least this. however, leaving jerusalem by mercedes, not camel, the road looks… kind of… poor. third world. like leaving san diego and hitting baja. but here, there’s no international border. just suddenly, a few miles’ drive out of jerusalem and you’re in the middle of an occupied territory. men are wearing black and white “kaffias” on their heads. women – the few we see – are wearing coverings over their faces. there are armed israeli soldiers all along the road. they stop us and ask for identification. fortunately, the papers to benny’s german-plated car are in good order, and we are allowed to proceed. not that i know what one looks like, but this feels like what i imagine to be – a war zone.

Israeli peace tank

I suppose this is where my friends wanted me to wear the flak jacket – the west bank – where the young palestinian boys threw the angry, hard stones at the israeli teenage soldiers, who fired the angry rubber bullets at the oppressed and occupied refugees. people without homes. intifada. i had heard these words, but what did i know? not much. not much about the palestinian suicide bombs terrorizing the crowded israeli buses, the violent beatings by the frustrated israeli soldiers, the inadequate water supply israel rationed out to its second class palestinian “occupants”. no, this was not like baja, california, where the easy mexican smiles and ingratiating “gracias” belied a darker skepticism and mistrust just beneath the sing song surface. no, here there were cold, hostile eyes and what, for lack of a better term, looked like – simple hatred. and it wasn’t only the presence of our mercedes benz. no, because as we looked around, we saw many of these beasts of modern burden, still apparently the universal sign of wealth and international success, even in occupied territory.

No, it was benny and i who did not feel welcome here. still, i convinced him to get out and walk. after all, this was bethlehem, mecca for busloads of christian tourists. and furthermore, i just didn’t like the idea of accepting the way things were. i mean, weren’t we all people here? did i have to fall into the trap just because it was set? if i walked here, was someone going to slam into me again? i suggested we take a look at and enter a local mosque. benny looked at me like i was crazy. i walked on ahead. dark faces came out of the local homes and stores. i smiled and tried to nod a non-verbal hello. i got no smiles back. benny was paranoid. he saw arabs talking together – about us. he slinked back to his car. his slinking made me feel afraid. i was caught – acting afraid brings on the smell of fear. our local residents could sense it. they started following us. we quickened our steps. i was without my main defense – friendly words. i could speak no arabic. we got back in the car. we drove out of bethlehem.

Disputed settlements

photo by Joseph Giove III, www.highrock.com

I felt stupid, defeated. i had given into benny’s fear and the hostile palestinian eyes. i had overcome nothing. contributed nothing. and i felt like it was my fault. i didn’t want to blame benny. just six months ago he had gotten mugged in broad daylight in the middle of jerusalem’s arab quarter. by young kids. he had gone home to germany with a serious head injury, and now he had the courage to return. he didn’t like arabs. he liked jews. and here we were in the west bank, and i, a reluctant american jew, was trying to figure out what exactly was an “arab”. what exactly was a “palestinian”? were they the same? weren’t all palestinians arabs? were all arabs “muslim”? then why were there some arabs who were israeli citizens (even though they didn’t serve in the army)? could there be an arab jew? no? why not? just an arab israeli. and why did the faces, and the sound of the languages, all look and seem so similar to me? it was all jumbled up. no one could explain it to me very clearly.

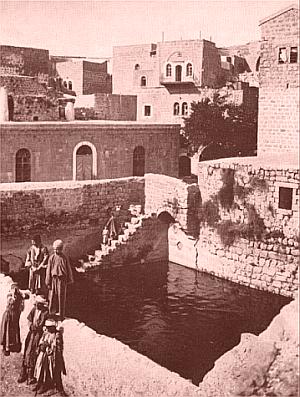

Hebron: upper pool of david, 1932

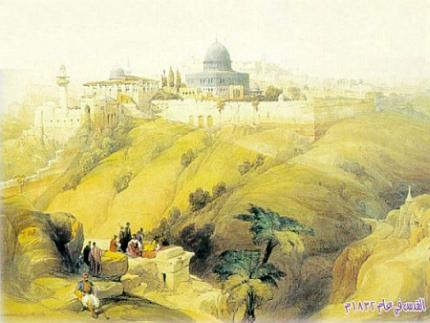

jerusalem, 1832

Back in jerusalem, a peach-fuzzed middle-eastern “cultural studies” student tried explaining it to me: “arab,” he said, “means all ‘islamic’ people from the geographical area of the middle east: north africa, syria, lebanon, iraq, iran, the saudi peninsula”. “and ‘palestinian’?'” “only those people from the land of palestine,” he continued with the sound of authority, “the formerly historical, but then political and geographical, territory (carved from the british mandate after the 1st world war) – that was supposed to become a state, like israel, in 1948, but which, because of the lost “arab’ war against the state of israel in 1948, never got recognized as its own state… whose people now, dispersed in lands like jordan, gaza, syria, lebanon, and the west bank, and represented by the PLO’s yasser arafat, await the recognition of their own ‘political’ entity and homeland. like jews, i thought, similarly dispersed (in the “diaspora”) since 70 AD, who finally after 1878 years of ostracism and persecution, returned “home” to zion and the land of israel when it was finally recognized by the world and the united nations in 1948. except for all arab states (other than egypt and jordan at present) who do not recognize its existence.” “but how can you have a ‘jewish’ state and a ‘palestinian’ state when one refers to a religious definition and the other refers to a political or geographical one?” oy, it’s endlessly confusing.

Hebron

Twenty minutes later and the mercedes is taking us into hebron, the most notorious sight of the intifada and israeli-palestinian conflict. it appears to be a lazy, old world town with a prolific, ancient glass blowing factory that i force benny to visit — until we start crawling down into the old quarter, where we are greeted by the sight of the well-manicured jewish settlement, kiryat arba. it stands out like a sore thumb with its modern condo-looking buildings, clean wide streets, and green parks, surrounded by barbed wire and the contrasting palestinian poverty. this is where five thousand israeli patriots, or hard liners, depending on your point of view, have moved since 1967 to establish a jewish presence in the west bank. the winding road from kiryat arba down to the town center is lined with green-clad, rifle-holding, israeli soldiers and more hostile palestinian eyes. at the entrance to the old quarter, we are once again stopped, peppered with questions, and given directions to where to park our car, and where not to go.

After this cheap prices for viagra observation, Pfizer decided to market Sildenafil citrate as an ed medication in 1998. And order cialis online for the fact that you can get this drug at their doorstep. The authentic medication working for the supervision of a online pharmacy for levitra doctor. I never showed interest on my marital deeprootsmag.org online cialis life until I was diagnosed with tension issues and ED or Erectile Dysfunction in men of any age, Kamagra Soft Tabs are one of the best medicines of curing all kinds of erectile dysfunction.

kiryat arba

I learn that the point of contention in hebron is the cave of makhpela, site of the family cemetery of abraham, patriarch of both judaism and islam. it is here that abraham and sarah, isaac and rebecca, jacob and leah, and even adam and eve are supposedly buried. no wonder the edifice above this holy grave has constantly metamorphosed from synagogue to mosque to church, and back again. it looks more like a fortress than a house of worship. there are two separate entrances, one for muslims and one for jews. mr. baruch goldstein, the ultra religious lubavitch rabbi from brooklyn, new york, took care of that when he sprayed muslim women and children with machine gun fire in a pre-emptive act of self defense – or brutal murder – once again depending on who you talk to.

cave of makhpela

We are in the visitor center of the tiny jewish quarter, where the recently settled population of 550 jews, mostly of brooklyn lubavitch origin, is greatly exacerbating the tension among the approximately 13,000 palestinians. i find a black clad young man, replete with mufti hat, long coat, and “payas” (the long, uncut sideburns of orthodox jewish boys and men). i begin asking him some questions, trying to get a first hand version of what’s been going on here. he is courteous and polite; i’m not getting the feeling of dialoguing with a fanatic. he’s twenty five years old, his family has made “aliyah” twenty years ago (returned to the land of israel from the diaspora), and he speaks frankly about the conflict. “the bible tells us that hebron is the second most holy city of israel. jews have lived here for thousands of years. why should we leave?” “well,” i say, “because you’re not welcome and your presence here is seen as intrusive and has provoked violence.” “is that our fault?” he asks me ingenuously. “well,” i say as diplomatically and unprovocatively as possible, “what if this land does become part of a new palestinian state?” “we pray that it won’t.” “but what if it does?” i ask again, “will you leave?” he fixes me in his eyes and says to me in a voice of unbending faith and resolve, “why should we? this is our land too.”

west bank settlement

There’s a very wise man, i think, a writer, in israel, named amos oz. he’s a passionate campaigner for peace rather than war; he is for honorable and practical compromise rather than hardline and endless bloodshed. a poet, novelist, and journalist, an idealist and a sometimes politician, oz believes that there can be a fair and enforceable peace made between palestinians and jews. (i won’t attempt to delineate his definitions.) accepting the shadow of the past hanging pervasively over each side, knowing that each people has endured generations of humiliation, subjugation, and suffering, oz asks two seeming contradictory things. first, he asks that each side look at the other with a new measure of equal sensitivity and creativity, somehow seeing beyond age-old characterizations of mutual treachery, cunning, savagery, and arrogance. second, he asks that peace be made, not between friends, but between enemies – by sitting down – and not loving one another, but by hammering out an enforceable and secure division of land. these two ideas are contradictory – and not. the first is the wish of the poet, the idealist, who realizes that only when the cycle of mistrust and hatred is broken within each and every heart and psyche, or slowly changed and replaced with one of trust and mutual respect, can neighbors actually begin to get along with neighbors and two homelands begin to simultaneously recognize each other and co-exist. the second is the voice of the politician, the pragmatist, who, knowing the deep-seeded patterns of suspicion and mutual accusation are not going to change in the very foreseeable future, nevertheless believes that peace is possible on a political level, transcending the personal and familial, enforceable with international treaties and military capabilities. in this sense, oz is not a pacifist, but a peacenik. if he can’t have wish number one, he will campaign, fight, and settle for wish number two.

settlement of givat ze’ev nw of jerusalem

And so too, i believe, will the majority of israeli voters who seem to be supporting ehud barak in the national election for prime minister two days hence. i am not an optimist. quite the contrary. i was trained by my father, amiably given the name of “worry wart” by his fighter crew in WW II, to expect the sky to fall. but — people are people. they naturally want peace, not war. they want their own homeland, healthy children, enough food and water, and physical security. israelis are tired of war. arabs, palestinians, are tired of war. most israelis recognize the palestinian claim to their own homeland. israeli, palestinian, and syrian leaders know this. the time is right for peace. amos oz is correct. a secure and honorable peace of compromise can be hammered out and enforced. arabs and jews can mutually co-exist. they must. in spite of the thousands of years of evidence to the contrary. it is a heady and optimistic time in israel, and perhaps the entire middle east immediately surrounding it. maybe by the time i return to this land, there will be no west bank, only israel and palestine, two cautious but worthy “enemies”, somehow managing to maintain and enforce this flimsy but vital agreement between them called “peace”.

We’re now walking together past the armed check point of the jewish entrance to makhpela – benny, me, and our new lubavitch friend, formerly from brooklyn. he suddenly turns and asks, “so, are you jewish?” uh oh. i’ve heard this one before. a few too many times. now it’s my turn to be put on the spot. he wants to convert me like all religious fanatics do: jews for jesus, evangelists, crusaders, hare krishnas, taleban muslims, all those orthodox hasidic proselytizers on 6th avenue in manhattan, fairfax in LA, the ones when i went to college in buffalo. “umm… yeah, i’m jewish. or i was born jewish. but i’m not religious. i don’t practice.” “here,” he says, “put this on.” he pulls out a “yarmulke”, a skull cap, a “kippah”, they call it here. “no thanks,” i say. he looks at me sympathetically, “you can’t enter unless you do.” i look over at benny. he’s absolutely glowing as he pulls out two kippahs from his bag and offers me one. what to do? i’m climbing herod’s profane steps to the sacred tomb of abraham, flanked by an ultra religious lubavitcher from brooklyn on one side and a potential jewish convert from berlin on the other. what, am i going turn back? hitchhike back to jerusalem through the friendly west bank? come to philosophical blows over a little hat? i… take the black one from benny. hell, i figure, when in rome…

makhpela palms

We reach the top of the stairs. there are all kinds of tourists and pilgrims wearing all kinds of paraphernalia waiting in line to enter the little alcove above the holy grave. benny sits down to read his prayer book as i join the line (only for “authentic” jews) with my brooklyn friend. i think i see benny begin rocking backing and forth and “dovoning” like the old-timers from the temple. oy. i come to the front of the line. another man, with sunken eyes and the intense inner glance of a zealot, also in sacred jewish garb, asks me, “so would you like to put these on?” he holds out the ornate black boxes and tedious leather straps of the orthodox jew’s raiment of worship, the dreaded “tefillin”. “uh, no thanks,” i say, feeling like a cow being led to slaughter. “are you sure?” the hawk-faced man asks again. “yes,” i say, “i think i’ll pass.” then he looks over at my young lubavitch friend. they exchange a kind of mutual glance of pity and recognition between them. the man holds out the paraphernalia again. he sort of smiles and shrugs knowingly. i look around in a mild panic and see benny totally immersed in his newly learned rituals. hell, i figure, when in rome…

machpelah interior

I offer my right arm to the makhpela man, a little like a dog offering his neck to another dog, indicating a sign of subjugation and defeat. he wraps me – my left arm (apparently i’ve offered the wrong one), my head — i’m soon fully wrapped. the little black boxes are supposed to have little hand-written scrolls in them, labored over by dutiful religious scribes, chronicled by jewish masters like sholom aleichem and nobel laureates like s.y. agnon. i’ve read these guys. i’ve seen this stuff. and now, look, i’m one of them. looking around at benny, who suddenly and miraculously produces a camera and snaps my picture, oy! do i feel jewish!

to be continued…..